✨ Divination in the Southern Baptist Church ✨

The first chapter of I've Got Questions just for you

As a way of saying thank you for how cool you’ve been during the absolute onslaught of I’ve Got Questions marketing, I humbly bring you the first chapter (enhanced!) for your personal enjoyment. The book comes out (finally) next Tuesday, February 4, so there is still a whole week to pre-order and get the audiobook (I read it!) for free. I’m really just trying to help you get the audiobook for free. That’s my main goal here.

Enhanced you say? How so? Well, I added visual aides and additional footnotes for funsies, because I like an experience. The extra footnotes are bolded, the footnotes that already live in the book are normal type.

Thank you again for pre-ordering, for posting, for being here, for clicking links, for sharing with your people, all of it. I kind of turn into a basket case when I think about this place and what it means to me, how you’ve been so kind. Maybe it’s silly to thank you for your attention and your contributions, but then I guess I’ll just have to be silly.

Thank you.

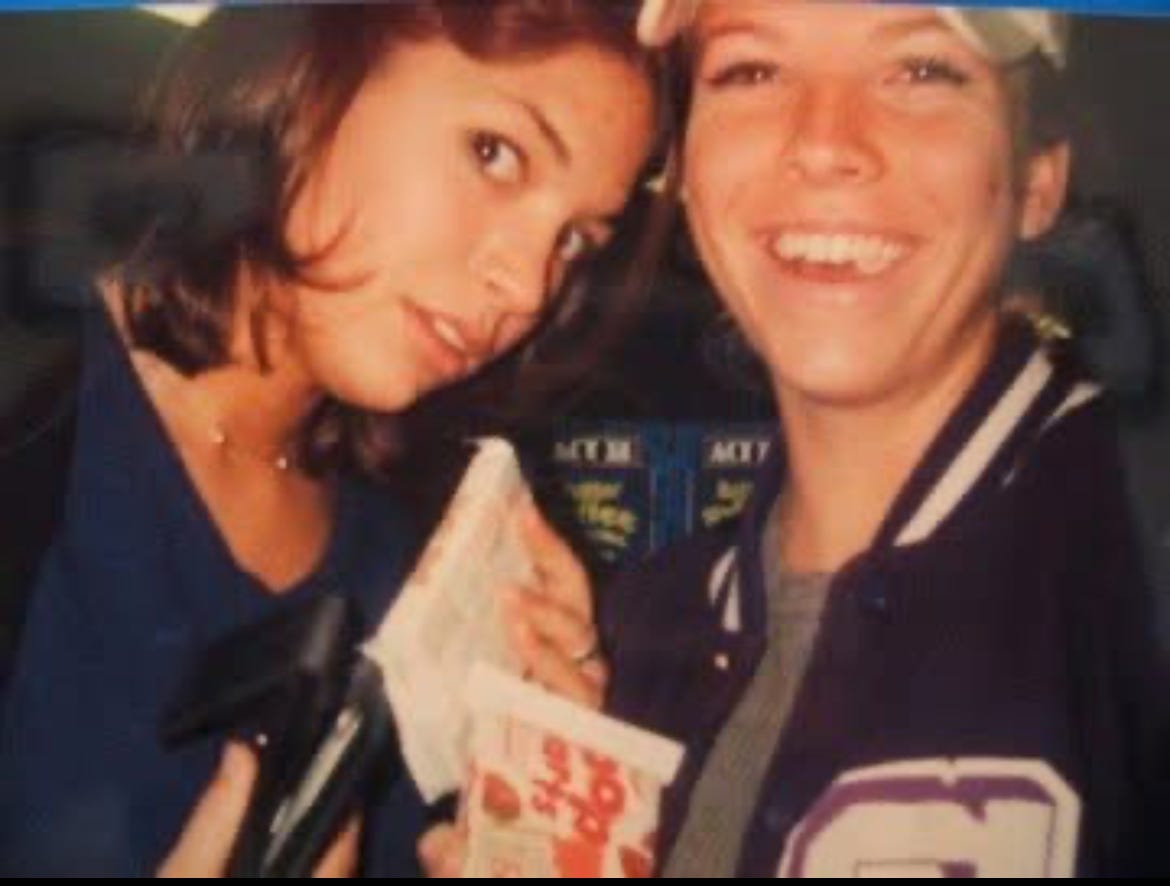

Also this email is too long and TOO AMAZING to fit in your inbox, so do click over to Substack so as not to miss my 7th grade Glamour Shot.

And now, without further ado, here’s the (enhanced!) first chapter of I’ve Got Questions: The Spiritual Practice of Having It Out with God.

You don’t often get fortune-telling in a Baptist church, so when it happens, you sit up and take notice.

Perhaps prophecy is a better descriptor. I was about thirteen years old, slightly more concerned with whether a boy was going to hold my hand in the church van on the way to the Hot Hearts Conference the next weekend1 than I was about paying attention to the traveling preacher behind the pulpit that Sunday.

Knowing me, I was also most likely trading notes with my best friend, Jen, on the back of the church bulletin, planning and plotting until the preaching was over so we could beg our parents to take us to The Railroad Crossing restaurant, which we knew was a pipe dream because my mom definitely had a roast in the Crock-Pot, but it worked once when we were ten, so we persisted.

Jen and I snapped out of our masterminding as the traveling preacher2 directed the congregation’s attention to the student section on the left-hand side of the sanctuary and asked all of us to stand. Our youth group of about fifty awkwardly stood, aware of every eye suddenly on us.

“These young people, right now, they are on fire for the Lord, aren’t they?”

A murmur rippled through the crowd. Heads nodded. It was a Baptist church, so of course we heard an amen or two. I don’t remember the exact phrasing, but I remember the gist of what he said next. That traveling pastor pointed at all of us standing students, these future millennials with no idea what was ahead, and addressed the grown-ups of our church. “If us believers don’t start living out the real truth, if the church as a whole doesn’t get its act together, if we continue to be distracted by things that don’t matter, if you and I don’t make Jesus Christ Lord of our lives instead of a lucky rabbit’s foot, this generation of young people will get up from these pews one day and ask us what we’ve done with the gospel. They will walk out of this place because they know the truth doesn’t live here. Church, we have the good news. It’s time we act like it.”

Like I said, a little bit of fortune-telling, yes? Fast-forward thirty-some-odd years, and here we are.

The data tells the story on its own. In 2021, churchgoing folks of the United States fell below the majority for the first time in our history.3 And it’s not just going to church. There’s a rapid decline in those who would check the box to describe themselves as Christians at all.4 Half of the religious demographic of “nones” left a childhood faith over a lack of belief. One in five said they “disliked” organized religion, and 18 percent indicated they are religiously unsure.5 It’s clear that traveling pastor was onto something. According to recent polls, 44 percent of people6 will go through some kind of faith transition during their lives, and 66 percent of young people7 who have a history of church attendance will leave by the time they are twenty-two years old. The numbers for Gen Z are even more alarming (well, depend- ing on who you’re talking to): 52 percent of young people who claim religious affiliation (and 80 percent who don’t) rate their trust in religious institutions at a 4.9 on a 10-point scale.8

Of course, unlike this traveling pastor, it would be unfair to lay the blame entirely on our elders. If you were old enough to sit in that student section, you know we’ve been through a lot, personally and globally: Columbine, 9/11, the financial crisis, and COVID-199, just to name a few of our collective traumas. And, for many of us, we got kicked in the teeth by the realization that the world is quite different from church youth group, and Sunday school answers don’t hold up in a hurricane of white Christian nationalism, sex abuse scandals, and the disillusionment of real life.

If the data sings the melody, then our lived experiences give this sad song its resonant harmonies. These numbers are more than just statistics; they represent flesh-and-blood children of God who feel alone, tired, and frustrated by the jarring difference between God and what cultural Christianity and partisan preachers made of “God.” A lot of people today aren’t exactly sure what their faith looks like, much less what it’s “supposed” to look like. These masses make up the barely there believers of all ages, races, and socioeconomic statuses who are disenchanted with the expressions of the faith they were raised in.

We’ve been walking around with a lot of questions10:

Why does an institution that claims freedom so frequently yoke its members with unnecessary burdens?

Why is there cognitive dissonance between what we read in the Gospels and the way our faith is lived out?

Why does Christianity have a reputation for hatred, bigotry, and hidden abuse?

What do you do when the church you love pretends not to notice when the vulnerable are abused?

What do you do when the church is complicit in the abuse?

Why is the church at large so obsessed with political power to the point of no longer looking like Christ?

Where is the face of Jesus Christ in the public representation of faith?

Why does a faith structure that claims to be loving get so much press for doing the exact opposite?

How can I align myself with Christianity when its key message seems to revolve around exclusion?

Why is this so hard?

Is Christianity a moral good?

How do you untangle the knots of grief, anger, and pain in a place that is supposed to bear the fruit of joy, peace, and kindness?

What happens when the faith you inherited turns to ash, and how do you cope when a crisis of faith feels like an emergency?

Is this (gestures wildly) what Jesus meant? Is this, as our bracelets asked, what Jesus would do?

What, pray tell, in the actual hell is going on here?

I’m sure you have your own questions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Swipe Up: A Newsletter from Your Internet Friend to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.